The Osage Nation is a Native American Siouan-language tribe

in the United States that

originated in the Ohio River valley in

present-day Kentucky.

The Osage Indians lived along the Osage and Missouri rivers in what is now western Missouri when French explorers first heard

of them in 1673. A

seminomadic people with a lifeway based on hunting, foraging, and gardening,

the seasonal movements of the Osage brought them annually into northwestern Arkansas throughout the

18th century.

|

|

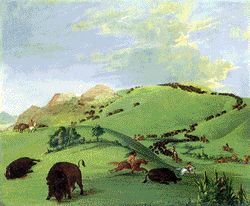

Three principal hunts, each organized by a council of

elders, were held during the spring, summer, and fall. The men hunted bison,

deer, elk, bear, and smaller game. The women butchered the animals and dried or

smoked the meat and prepared the hides. The women also gathered wild plant

foods and at the summer villages tended gardens of corn, beans, squash, and

pumpkins. Surplus products, including meat, hides, and oil, were traded to

other Indians or to Europeans. The Osages acquired guns and horses from

Europeans during the eighteenth century, which enabled them to extend their

territory and control the distribution of European goods to other tribes in the

region.

Most men shaved their heads, leaving only a scalplock

extending from the forehead to the back of the neck. The pattern of a man's

scalplock indicated the clan he belonged to. Men wore deerskin loincloths,

leggings, and moccasins, and bearskin or buffalo robes when it was cold. Beaded

ear ornaments and armbands were worn, and warriors tattooed their chests and

arms.

Women kept their hair long and wore deerskin dresses,

woven belts, leggings, and moccasins. Clothing was perfumed with chewed

columbine seed and ceremonial garments were decorated with the furs of ermine

and puma. Earrings, pendants, and bracelets were worn, and women decorated

their bodies with tattoos.

Osage communities were organized into two divisions called

the Sky People and the Earth People. According to their traditions, Wakondah,

the creative force of the universe, sent the Sky People down to the surface of

the earth where they met the Earth People, whom they joined to form the Osage

tribe. Each division consisted of family groups related through the males,

called clans, that organized social events and performed rituals for special

occasions. Each clan had its own location in the village camping circle and

appointed representatives to village councils which advised the two village

leaders - one representing each tribal division.

Villages were laid out with houses on either side of a

main road running east and west. The two village leaders lived in large houses

on opposite sides of the main road near the center of the village. The Sky

People clans lived on the north side of the road, and the Earth people clans

lived on the south side. Council lodges for town meetings were also constructed

in the larger villages.

|

Detail from

"Osage Dreams," by Charles Banks Wilson. Courtesy of the artist.

|

Osage houses were rectangular and sheltered several

families. Measuring up to 100

feet long, they were constructed of saplings driven into

the ground and bent over and tied at the top. Horizontal saplings were

interwoven among the uprights, and the framework was covered with hides, bark

sheets, or woven mats, with smokeholes left open at the top. Most houses had an

entrance at the eastern end. A leader's house had entrances at both ends.

Village life followed rules and customs established by

a group of elders known as the Little Old Men. To join the ranks of the Little

Old men, serious-minded individuals had to undergo training that began during

boyhood and lasted for many years. Little Old Men passed through seven stages

of learning, at each stage acquiring mastery of an increasingly complex body of

sacred knowledge.

Ceremonies were performed for important activities and

events, including hunting, war, peace, curing illnesses, marriages, and

mourning the dead. Many ceremonies required elaborate preparations and

participants would often wear special clothing and ornaments or paint elaborate

designs on their bodies. Each clan had specific ceremonial duties that in

combination served to sustain the wellbeing of the tribe.

Osage lands in Arkansas

and Missouri were taken by the U.S. government in 1808 and 1818, and in 1825 an

Osage reservation was established in southeastern Kansas. Today there are about 10,000 Osages

listed on the tribal roll, many of whom live in and around Pawhuska, Oklahoma.